@Tomlenegg Beyond normal sparging there is also a traditional sparging method in the UK called the parti-gyle method where you collect the first, second, and often third runnings from a mash and use each for its own beer.

The first runnings have the most sugar, and become your strong beer, the second runnings a standard ale, and the third, a mild. Some brewers like Fuller's use a modified parti-gyle and will blend their runnings in different %s for their beers instead of 100% from one batch.

@Tomlenegg So glad you asked! In general, you want to sparge until your kettle has the volume of liquid you want for the boil. We can assume after the mash that the grain is saturated and can't hold more water, so new water in = water out. So take the final volume of water you want at the start of the boil, subtract however much water you collected in the first runnings, and the difference is how much water you want to use for sparging.

@JoanESheldon When we harvest the hops we dehydrate them and then store them in vacuum bags in the freezer until it is time to use them. Moisture and exposure to oxygen and UV rays are apparently the main things to avoid.

@neilbearse I used White Labs WLP840 American lager yeast. This is a pretty by the book version of "Pizza Boy Dark" all grain recipe from Brewing Classic Styles except I subbed in my homegrown hops. A majority of my brewing comes from that book even after brewing for years because I get consistently good results.

All that's left is for me to clean my equipment. With the Grainfather this means pouring some water into it, adding some brewing cleaning (PBW in my case) heat the water, and then pump it through it and the counterflow chiller for 10 minutes, replace with fresh water, and then rinse for 10 minutes.

Thank you everyone who stuck with the thread to this point. It was fun sharing the brewing day with everyone. Feel free to post any questions you may have.

@aeberbach Thanks! I started with a plastic bucket beginner brewing kit, a cheap 7 gallon aluminum boil kettle, and dry malt extract kits and that's what I recommend everyone else do to start.

How to Brew by Palmer is a classic and the best book to learn the process and science behind brewing. Brewing Classic Styles is a great book full of extract/all-grain recipes and it's still the main place I go for recipes (including the one today). Modern extract kits are really good.

With the last bit of wort pumped into the carboy, I pitch my yeast, add an airlock to the top, fill it with vodka, and the brewing process is done. I will move the carboy to a temperature-controlled chamber where it will ferment for a few weeks, then lager for a few more weeks, before I transfer it to a keg.

As the wort pumps into the carboy, I redirect a bit into a cylinder so I can take a gravity measurement (in this case I was right on target: 1.050!). This measures the specific gravity of the liquid compared to plain water and approximates the amount of sugar you have in your wort. Later when the beer is done fermenting I will take another reading and use the difference to determine how much sugar was converted into alcohol.

With enough cool water flowing through the system, the counterflow chiller can chill the wort enough to go into the fermentation vessel (plastic carboy) within a few minutes. I have an in-line thermometer I use to monitor the temperature of the wort leaving the counterflow chiller and when it's within the right range I stop the pump, move the wort output to my carboy, and start the pump again, pumping the cool wort into the carboy.

The counterflow chiller is a heat exchanger with two inputs and two outputs. Hot wort is pumped through one input and exits back into the kettle. The blue tube is an input attached to a cool water source (garden hose) and the red tube is the output of that water source. As the hot wort and cool water flow through the chiller, the heat is exchanged, cooling the wort and heating the water. I collect the hot wastewater and re-use it for cleaning the kettle later.

The boil is done so I've attached my counterflow chiller to my Grainfather pump and I'm recirculating boiling wort through it for 10 minutes to sanitize the inside of it before I connect it to cool water to actually chill the wort. I also filled my fermentation vessel with sanitizing solution for 10 minutes so it will be disinfected when I'm ready to transfer wort to it.

I have about 30 minutes before I need to do the next step in the brewing process, and everything I can clean is clean, so now's a good time if anyone had any questions or wanted more specific details about brewing in general or my brewing specifically.

Now for the first (and for this recipe only) hop addition with 60 minutes left in the boil. These are whole leaf Cascade hops that we harvested from our hop plant in our garden this summer.

Adding hops at this stage of the boil extracts compounds that make the beer taste more bitter. These compounds are also anti-microbial and help protect the beer from infection post-boil, especially in the sensitive stage before the yeast make any alcohol.

We are about 30 minutes into a 90 minute boil. If you look closely at this picture you can see light tan bits that aren't foam, that seem to be floating to the top. This is known as "hot break" and are proteins that are cooking out of the wort during the boil. This is something we want to happen and is one of the reasons for the boil.

@neilbearse Because I'm in the US and just have 110V going into it, it took about 1:15 to go from the start of the sparging process to the boil. I should note though that this kettle was almost completely full, due to the extra liquid to allow a 90 min boil. I actually removed a few liters of wort because I was concerned about a boil over.

I just reviewed my brewing notes from past brews and it seems it's an hour to an hour fifteen from start of sparge to boil normally.

The lautering/sparging process is complete so I removed the top grain basket and now we are waiting for the wort to reach a boil. What do we do while we wait? We clean of course! I dumped the spent grain into the compost bin and cleaned the grain basket and lauter kettle and all mashing and lautering equipment. In a minute I will start stirring the foam at the top of the kettle back into the wort so it doesn't boil over when it hits boiling temps.

After mashing, I lift the interior metal basket and rest it at the top of the Grainfather. There is a mesh at the bottom of this basket which allows the sticky, sweet brown liquid called wort to drain into the kettle while leaving the grain behind.

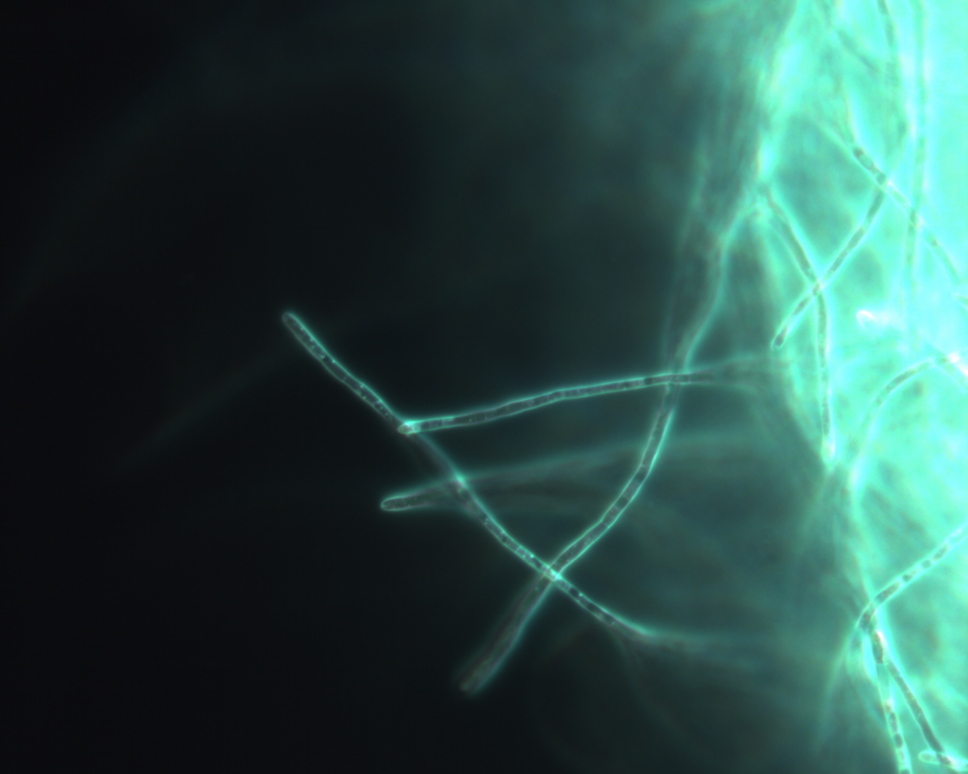

While the kettle heats up to boiling, I start rinsing the top of the grain with hot water from my lauter tun. This water trickles through the grain bed and extracts more sugars as it drips down into the kettle.

After mashing, the next step is the lautering process, where I remove the grain from the mash water and rinse it with hot water to extract more remaining sugars.

This is my lauter tun. It's an electric brewing kettle that I used to brew beer with before I got my Grainfather. I fill this kettle with the appropriate amount of water, heat it to the proper temp, and then connect a hose to a spout at the bottom and use gravity to move the water to my Grainfather.

Even though I need to wait 90 minutes for the next step of the process, I'm not sitting here idle. A key part of having an enjoyable brew day, I've found, is to clean up incrementally during these down times, and prepare everything for the next step. For instance, after I started the mashing process, I put away all of the grain grinding equipment and my bag of bulk barley, swept loose grain from the floor, and now I'm preparing my lauter tun for the next step.

During this 90 minute mashing process enzymes in the malted barley convert starches into simple sugars like alpha and beta amylase. The ideal temp to convert each of these sugars is different, so recipes pick temps somewhere in the middle based on which sugars they want the most of. This choice can affect the body and residual sweetness left in the beer after fermentation.

- Personal Site

- https://kylerank.in

- Personal Bibliography

- https://kylerank.in/writing.html

Technical author, FOSS advocate, public speaker, Linux security & infrastructure geek, author of The Best of Hack and /: Linux Admin Crash Course, Linux Hardening in Hostile Networks and many other books, ex-Linux Journal columnist.